In my view, were one to be forced to choose the three most indispensable reference wine books published in English, they would be these:

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th ed., edited by Jancis Robinson and Julia Harding, with Tara Q. Thomas. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023.

- Hugh Johnson & Jancis Robinson. The World Atlas of Wine: A Complete Guide to the Wines of the World, 8th ed. London: Mitchell-Beazley, 2019.

- Jancis Robinson, Julia Harding, & José Vouillamoz. Wine Grapes: A Complete Guide to 1,368 Vine Varieties, Including Their Origins and Flavours. NY: Harper Collins, 2013.

Some may quibble that The Sotheby’s Wine Encyclopedia: The Classic Reference to the Wines of the World, 6th ed., 2020, by Tom Stevenson and edited by Orsi Szentkiralyi, would be preferable to the Wine Companion, but I feel that the Wine Companion together with the World Atlas make for a more comprehensive exploration of the world of wine.

NOTE: None of these books are for the wine neophyte, for that, I’d recommend Kevin Zraly’s Windows on the World Wine Course, 35th Edition. NY: Union Square, 2020. One of the great advantages of Zraly’s approach is that he explains how to taste wine in some depth with a unique approach. It has been described in the NY Times as “One of the best start-from-scratch books ever written.”

As one can see, all three books are by British writers, with the exception of Vouillamoz, who is Swiss, and a highly respected ampelographer and vine geneticist.

One reason for the very high standards of style and scholarship has to do with the fact that Robinson, Johnson, and Harding are all Oxbridge stuff. The other reason the standards are so high is because it’s the Brits who have been writing about wine almost longer than anyone, certainly in English. It helps, as well, that they are not given to hyperbole or chest-thumping, just really good writing and scholarship. It is also a fact that Robinson and Johnson are perhaps the two most-widely read authors in the wine world, certainly in our language.

I chose these three books because I consider them to be comprehensive and complete, with top-of-the-class expertise, quality layout and printing, and very high levels of scholarship. For example, the Washington Post, in its review of the first edition of the Wine Companion, referred to it as the “definitive guide to the world of wine.” This remains true today, with the 5th edition just published in 2023. The new edition is substantially revised and updated.

I do not propose to review here the Oxford Wine Companion or The World Atlas of Wine, which was newly published in an 8th edition in October 2013. I’ve already said something about each in my post, Wine Books that I Recommend. Suffice it to say that both books are widely recognized as indispensable and essential wine references.

This is particularly true of Wine Grapes, published as a hardcover edition with a slipcover and a beautiful layout, with scholarship galore to support one of the most difficult subjects in wine. It is expensive: on Amazon .com it can be found for $111, a substantial discount from its list price of $199. However, if one is truly serious about wine, as a wine-lover, wine writer, or a professional in the trade, it behooves one to get this book. It’s entirely worth the price.

Review of Wine Grapes

Robinson had already ventured into the subject of wine grapes with two earlier books, both for the “popular” press rather than for specialists: the first was Vines, Grapes, & Wines: The wine drinker’s guide to grape varieties, published in 1986, followed by her compact Jancis Robinson’s Guide to Wine Grapes, in 1996, based on the grape entries in the first edition of The Oxford Companion to Wine (1996). Her only serious competition in English was Oz Clarke, who published Oz Clarke’s Encyclopedia of Grapes: A Comprehensive Guide to Varieties & Flavors with Margaret Rand in 2001, which was later updated as Grapes & Wines: A comprehensive guide to varieties and flavours in 2010. All of these books primarily were aimed at the sophisticated wine consumer, and though all are highly informative, amply illustrated, and enjoyable to browse or do basic research, none was suitable for a professional audience nor offered the level of intellectual insight that Wines Grapes does.

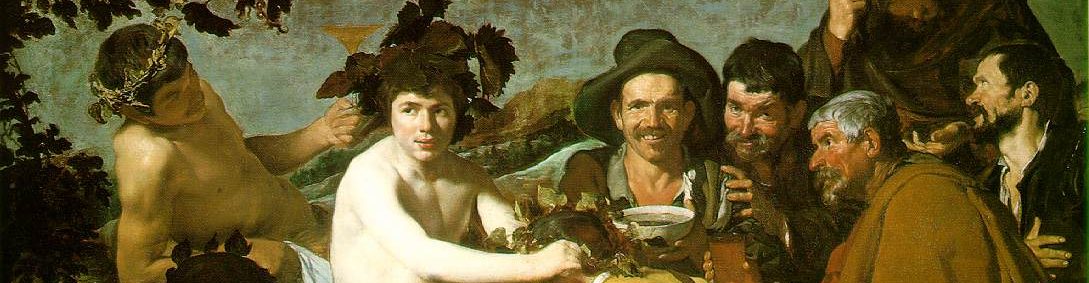

The definitive reference for professionals, until now, was the great magnum opus in seven volumes, published in French, by Pierre Viala and Victor Vermorel: Ampélographie, between 1901 and 1910. It covered 5200 wine and table grape varieties, with focus on the 627 most important one, accompanied by over 500 paintings depicting the grapes as bunches with their foliage. A selection of those paintings was incorporated into this volume under review.

This book discusses the 1,368 varieties that are still in commercial production, however small the plantings or the production. For every single variety, it lists its 1) principle synonyms, 2) varieties commonly mistaken for said variety, 3) its origins and parentage, 4) other hypotheses [if any exist], 5) viticultural characteristics, and 6) where it’s grown and what its wine tastes like. I’ll take, as an example, the entry for Baco Noir:

“Dark-skinned French hybrid faring better across the Atlantic than at home.”

“Berry Colour: [black]

“Principal synonyms: Baco 1, Baco 24-23, Bacoi, Bako Speiskii, Bakon

“Origins and Parentage

“Hybrid obtained in 1902 by François Baco in Bélus in the Landes, south-west France, by crossing Folle Blanche (under the name Piquepoul du Gers) with Vitis riparia Grand Glabre. It is therefore a half-sibling of Baco Blanc. However, as noted by Galet (1988), since V. riparia Grand Glabre has female-only flowers with sterile pollen, Darrigan considered this hybrid to be Folle Blanche x V. riparia Grand Glabre + V. riparia ordinaire, which suggests that Baco used a mix of V. riparia pollen taken from two distinct varieties. . . . .

“Viticultural Characteristics

“Early budding and therefore at risk from spring frosts. Best suited to heavy soils. Vigorous and early ripening. Good resistance to downy and powdery mildew but highly susceptible to black rot and crown gall. Small to medium bunches of small berries that are high in acids but low in tannins.

“Where It’s Grown and What Its Wine Tastes Like

“Baco Noir was at one time planted in France, in regions as diverse as Burgundy, Anjou, and its home in the Landes, but the area has dwindled considerably, down to around 11 ha (27 acres) in 2008 . . . .

“The variety has fared better in cooler parts of North America since its introduction in the 1950s. New York crushed 820 tons in 2009 (almost double the amount for 2008) in both the Hudson River and Finger Lakes regions and in southern Oregon . . .”

But even before one gets to the profiles of those 1,368 varieties, there is the excellent Introduction, with subject headings such as:

- The Importance of Grapes Varieties, which covers the background of how varieties came to take such a prominent place in a wine world that had once only paid attention to regions, such that the French, with their AOC system would identify a wine as from Pauillac, and the knowledgeable imbiber would know that this was a claret or red wine from Bordeaux—varieties be damned; in the USA wines were made that were identified merely as Claret or Burgundy, though the varieties could be anything but those from Bordeaux or Burgundy. There is even a box that clarifies the difference between variety (the grape) and varietal (the wine). There is also a chart showing the climate-maturity groupings of varieties.

- The Vine Family, discussing some (but not all) of the vine species used to make wine, with emphasis on V. vinifera and its two subspecies, sativa (the cultivated vine) and silvestris, the wild or forest vine.

- Grape Variety, Mutation and Clone, a fascinating discussion that explains how a vinifera variety comes into being, as well as explaining the differences between mutations and clones. One of the most interesting observation is the discovery that Pinot Noir, Pinot Gris, and Pinot Blanc are all genetically identical according to standard DNA profiling, and are only distinguished by a single gene that changes the amount of anthocyanin that imparts color to the grape skins. This section also dispels some myths about varieties and there tendency to mutate.

- Vine Breeding, which explains how the domesticated vine has been deliberately bred for particular characteristics, often by selected intraspecific crossing (vinifera with vinifera) or by interspecies crossing (e.g., vinifera with riparia). It also discusses successful vs. unsuccessful results, as in the case of the effect of the German Wine Law of 1971, which caused breeders to aim for varieties that would produce high sugar levels regardless of the overall effect on the quality of the resulting wines.

- Pests and Diseases, an important category in any discussion of vines and vineyards, provides a background of how certain diseases and infestations were spread thanks to the intervention of human activity in the transportation of unwanted guests that often accompanied vines transferred from America to Europe for experimental plantings in order to see how American vines would do in European soil. Perhaps it would improve them. Alas, along came downy and powdery mildews and the charmless, almost invisibly tiny, parasitical mite that came to be called Phylloxera devastatrix, which nearly devastated the vineyards of France, Germany, and Italy.

- Rootstocks, Grafting, and Fashion, a brief account of the significance of rootstocks—which could deserve an entire book in their own right—grafting, and how fashions in taste can be mollified for a time (remember the days of ABC—Anything But Cabernet/Chardonnay) by the simple expedient of top-grafting, rather than uprooting the entire vine and waiting three years for it to begin to bear fruit.

- Vine Age, an explanation of how older vines offer the vineyardist a two-edged sword: higher-quality grapes at reduced production levels.

- Changes in Vineyard Composition, discusses how vineyards are moving away from field blends (multiple varieties in a vineyard plot) to monovarietal cultivation as well as the resurrection of nearly extinct varieties that are still of interest for winemaking.

- Labelling and Naming bears primarily on the marketing of wine. Where once Europeans rarely mentioned varietal names on the label and emphasized regional origin instead, the success of varietal emphasis in the New World eventually was accepted as the standard for all but the most traditional, expensive wines offered—say a Château d’Yquem (Sémillon, Sauvignon Blanc, Muscadelle anyone?) or La Tâche (Pinot Noir, period).

- DNA Profiling, is about the shift from ampelography (the identification of a vine by its leaf and bunch characteristics) to the use of DNA to establish parentage and sibling relationships. Throughout the book there are family vines (trees) to show the relationship of, say Pinot to Syrah (!), no matter at how many generations removed. DNA profiling can’t answer all these questions, since a parent variety that is now extinct or unknown cannot be linked to its supposed progeny, so question marks abound in the charts.

The next chapter, four pages of text and three of charts, is Historical Perspective, with the following headings:

- Grapevine Domestication: Why, Where and When? This covers the various theories that have been put forth by various scholars. The first one, the ‘Paleolithic Hypothesis,’ holds that sometime in pre-history spontaneously-fermented wine was tried and produced the proverbial euphoria we all know so very well. This oeno-archeologist, Patrick McGovern, was a bit of a wag, referring to this drink as “Stone-Age Beaujolais Nouveau.” It had to be consumed immediately upon release lest it turn into vinegar. This is followed by the “Hermaphroditic Hypothesis” which argues that in the Early Neolithic, when societies began to settle down, early attempts to cultivate wine grapes quickly eliminated the planting of male vines, because they could never reproduce; female plants could only reproduce if there were male vines nearby; hermaphroditic vines, which today comprise the vast majority of cultivated vines, needed only themselves, and reproduction was virtually guaranteed. Then there is the issue of where the domesticated wine vine was first cultivated, and while the answer is not entirely certain, there are various ideas as to where, and it largely centers on the regions near Anatolia, Georgia, the northern Fertile Crescent, and so on. The when actually depends on actual archeological finds in that general region, which suggest as early as ca. 8000 bce, with other proposals holding that it may not have been until ca. 3400-3000, again depending on which evidence is most generally accepted.

- Western Expansion of Viniculture covers the general peregrinations of the wine vine from its ancestral home to Mesopotamia, then Egypt, and then Greece, Italy, France and on into Germany, Spain, and Portugal. Eventually, first with Spanish missionaries and later with immigrants to what would become the United States, cuttings and seeds were brought to the Western Hemisphere. Chloroplast DNA studies are cited as evidence of a possible secondary domestication of V. vinifera silvestris, but even this is in dispute.

- Ampelographic Groups is a really interesting section that deals with what is referred to in the book as the “eco-geographical groups” or proles, first proposed by A.M. Negrul in 1938 and again in 1946. Although some of the proles varieties may, thanks to DNA fingerprinting, belong to another group than that originally proposed, for the most part it seems to hold up, with three groups proposed: Proles occidentalis Negr., Proles pontica Negr., and Proles orientalis Negr. All wine-grape varieties emanate from one of these three groups, with Cabernet Franc and Chardonnay in the western group, Rkatsiteli and Furmint in the bridging group, and Chasselas and Muscat Alexandria, for example, in the eastern group. An accompanying map shows the geographical distribution of these eco-geogroups in France, along with a table listing the ‘sorto-types’ of the different varieties in the larger classification. Complex, isn’t it?

This is followed by a list of the Varieties by Country of Origin, and here we learn that the single largest group belongs to Italy, with 377 varieties, followed by France with 204 varieties; the USA has 76 native varieties, and the UK has a single one, Muscat of Hamburg.

Thence, the alphabetical listing of all 1,368 wine varieties still in production at whatever scale. The example of Baco Noir has already been given. Pinot, with its great clonal diversity, includes 156 varieties in its family (shown as a 3-page chart), which includes Teroldego, Savagnin, Gouais Blanc, Chardonnay, Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, and so on. All this is based on DNA analysis, which, given the many lost or extinct varieties that belong in the tree, leaves open questions of parentage or sibling relationships. For example, If Pinot is one parent of Teroldego, which variety is the other parent? With the various members of the Pinot family that includes Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier, Pinot Gris, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Teinteurier, and Pinot Noir Précoce, the entries for the Pinot family go on for 17 pages.

So it goes for all the varieties described, running 1177 pages, followed by a Glossary and an extensive Bibliography of 20 pages in length. References go from Acerbi, G., Dele viti italiane ossia materiali per servire alla classificazione mongrafia e sinonima of 1825 to Zúñiga, V C M de, 1905, on Tempranillo. The bibliography is up-to-date to 2012. Every variety under discussion has its citations from the bibliography.

Occasionally it passes up a nice nugget of information, such as the fact that in 1982 it was discovered that vines identified as Pinot Chardonnay were actually Pinot Blanc, but it took a few years for the newly-planted vines to produce fully-developed leaves, which allowed Lucy Morton—a viticulturalist who translated Pierre Galet’s book, A Practical Ampelography: Grapevine Identification, from French to English—to correctly identify the vines as Pinot Blanc by the shape of the vine leaves. (Incidentally, what was called Pinot Chardonnay—on the assumption that Chardonnay is a member of the Pinot family—is now called just Chardonnay). This little nugget could have been found under either the entry for Chardonnay or Pinot Blanc, but is in neither. Also omitted is any mention of the red vinifera variety Morenillo, which although “extinct” is actually still producing small quantities of wine in the Terra Alta DO. These are rare lacunae for such a thorough book.

This is not only a supreme work of scholarship, scientific research, and historiography, it is a remarkable accomplishment and an essential addition to the English world’s library of wine books. If you can afford it, buy it. You can’t afford not to.