Castello Borghese started as Hargrave Vineyard in 1973, the very first vineyard and winery in Eastern Long Island. By 1999 the Hargraves, Louisa and Alex had established not only that vinifera grapevines could be grown in Long Island, they had also proven that fine wine could be made from the fruit of those vines. It was a remarkable achievement and it gave rise to an industry that as of this writing includes over 60 vineyards, 24 wineries, one crush facility, and 53 tasting rooms serving a total of over 70 brands of wine. But time and the stress of raising a family and running a winery and vineyard had taken its toll on the Hargraves and in 1999 the property was put up for sale. (A few years later Louisa would write a book, The Vineyard: The Pleasures and Perils of Creating an American Family Winery, based on the experience.)

The winery and its land in Cutchogue were put up for sale. That was when Marco Borghese and his wife Ann Marie were visiting friends in the Hamptons who suggested that they pay a visit to the North Fork and taste some wines. (At the time they were living in New York City and had a wine shop which carried fine wine from around the world. It was there, as Marco said, “that the palate was born” for fine wines.) They twice visited Hargrave Vineyard, tasted the wines, were impressed by everything there. Jane Starwood, in her book, Long Island Wine Country, provides this anecdote about the purchase of the winery:

For a while after the purchase the property was designated the Hargrave/Borghese Vineyard and Louisa Hargrave was a consultant, but once they parted ways the name was changed to what it is today, with the designation, “The Founding Vineyard.” It is readily identifiable from County Road 48 (aka the North Road) not only by the sign but also the old truck with weathered barrels displaying the name of one of the varieties that is grown in the vineyard.

For a while after the purchase the property was designated the Hargrave/Borghese Vineyard and Louisa Hargrave was a consultant, but once they parted ways the name was changed to what it is today, with the designation, “The Founding Vineyard.” It is readily identifiable from County Road 48 (aka the North Road) not only by the sign but also the old truck with weathered barrels displaying the name of one of the varieties that is grown in the vineyard.

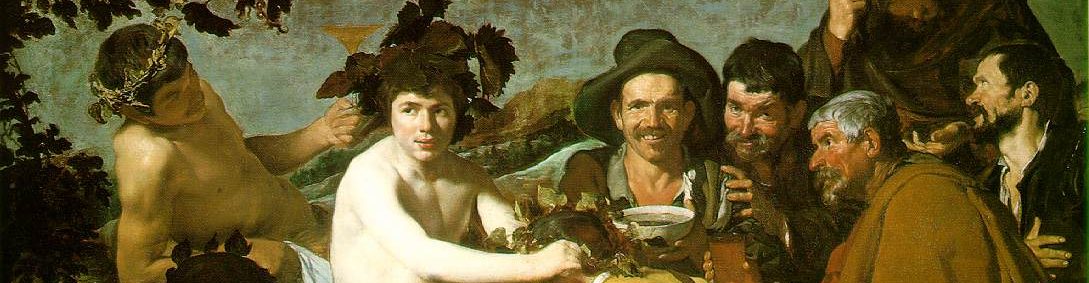

Marco Borghese, of the great noble family that began its prominence in Siena in the 14th Century, and included a 17th-Century Pope, Paul V, and a Cardinal, Scipione Borghese, who established the great art collection with works by Bernini, Caravaggio, Raphael, and others now held in the Galleria Borghese in Rome, was himself entitled to refer to himself as Prince, but sensibly did not, though royalty-besotted Americans insisted on the title for both him and his American wife, Ann Marie. Marco was in fact an unpretentious man of aristocratic mien, according to all accounts, and worked as a businessman living in Philadelphia, he in the leather business and Ann Marie in jewelry. They were also raising two young children, Giovanni and Allegra. Marco had a son, Fernando, by an earlier marriage, who lives and works in Philadelphia.

Marco soon found himself working in the vineyard and in the cellar, and Ann Marie was an events manager at their new property who also hosted weekend vineyard walks. Again, Anne Marie’s wit led to this remark, “Marco thought he was going to be a gentleman farmer. Instead he became a gentleman farming.” Like many other small wineries, they held parties, events, and weddings. They were determined to create a unique place on the North Fork: Old World charm and New World accomplishment.

I contacted Marco months in advance of an appointment to interview him and he was warm and full of good cheer when I spoke to him. When I next spoke to him in June 2014 his demeanor over the phone was very different: somber and distracted. I arrived for the appointment on June 18 only to learn that he had left abruptly on a “family matter.” Two days later Ann Marie, who had been fighting cancer for months, died at a hospital in New Mexico where she was being treated. She was only 56. A week later Marco was killed in an automobile accident in Long Island. He was 71. The entire wine community in Long Island was devastated by the double tragedy, not to speak of the family, and the question of the continuation or even the survival of Castello Borghese hung over the region for a while.

But there are the children: Fernando, Marco’s son by a previous marriage, and Giovanni and Allegra. Each of them had careers or planned on careers that had nothing to do with the winery. Each of them had careers or planned on careers that had nothing to do with the winery. All three decided that Castello Borghese had to survive and prosper, at the very least to honor their parents, but also because they felt a responsibility to the community and the people who had loyally worked at the winery for years. This was especially true for Allegra and Giovanni, who chose to set their careers aside in order to honor their parents by keeping the winery in business.

But there are the children: Fernando, Marco’s son by a previous marriage, and Giovanni and Allegra. Each of them had careers or planned on careers that had nothing to do with the winery. Each of them had careers or planned on careers that had nothing to do with the winery. All three decided that Castello Borghese had to survive and prosper, at the very least to honor their parents, but also because they felt a responsibility to the community and the people who had loyally worked at the winery for years. This was especially true for Allegra and Giovanni, who chose to set their careers aside in order to honor their parents by keeping the winery in business.

When I first went to Castello Borghese to interview the two offspring of Marco and Ann Marie, both Giovanni and Allegra greeted me very courteously. It was November 2014 and barely five months had passed since the death of both their parents. Neither had expected nor planned to be running their parents’ winery and vineyard and they were proceeding very cautiously to take over the running of the enterprise. They had the support of their older brother, Fernando, but he was already committed to his own career and could not attend to the day-to-day operations of the winery.

At least Giovanni and Allegra had had the good fortune to grow up in Cutchogue, as they were 14 and 12 respectively when their family moved there from Philadelphia after purchasing the winery. Both had gone to high school there as well. The two now lived in the house that had been their parents’. Fortunately they had the support of the community, which is pretty tightly knit. They also have the commitment and dedication to carry on from the employees, especially Bernard Ramis, the vineyard manager, Erik Bilka, the winemaker who is on contract though he also has a full-time position at Premium Wine Group, and the tasting-room manager, Evie Kahn.

As Giovanni explained, “I feel like we owe it to our parents to really give it a shot. Could we sell? Sure, maybe, like if the time and the number is right, like we’re not destined to be vineyard owners and aren’t really attached to running this kind of business and lifestyle. But I think that in the year here that there is so much still, [of] their energy, it feels like part of the process to really just be here and see this little baby of theirs survive and do okay. Just because it’s not necessarily what our plan was doesn’t mean we’re going to jump ship and say, peace. I didn’t have plans for that.”

Then there was this exchange:

Giovanni: “There are employees here who . . .”

Allegra: “Are like our family.”

Giovanni: “Depend on this job . . .”

Allegra: “And love it here. So I think we owe them leadership.”

Clearly, they speak with one voice.

Allegra went on to explain: “It was in our background. It’s kind of like when you’re a kid and you don’t know how to talk yet and you’re hearing language and then you’re going to need to learn to use it to talk. It’s like that. All the nuts and bolts were there but actually putting it into the practical application of it is new. And you make mistakes or it’s not perfect right at the initial stage. But I feel like we are slowly learning to speak this language and do this role in a more sustainable and professional and natural way.”

In fact, employees have volunteered that they’ve found Marco and Anne Marie’s offspring to be just as thoughtful, kind, and considerate as were the parents. They have a strong commitment to Castello Borghese and the loyalty is clearly strong in both directions.

On a second visit to Castello Borghese some months later both Allegra and Giovanni had clearly gotten past the wariness and somewhat tentative attitude about keeping and running the winery. For one thing, they had taken it off the market and it is no longer for sale. They are definitely in it for the long haul.

In fact, though they want to follow in their parents’ way and they listen to the advice of the long-time winery team, they are also open to innovation. Consequently, they are offering local beer by Greenport Harbor in the tasting room because they recognize that some visitors come along with their wine-loving friends but don’t necessarily like wine themselves. Indeed, were there no local beer they probably wouldn’t offer it, because they really are most interested in supporting local businesses.

On the other hand, Allegra, who recently earned her graduate degree in counseling and art therapy from Southwestern College in Santa Fe, is continuing a project that was very dear to Ann Marie: art exhibitions at the winery, but with an important difference. In March 2015 there was a display of paintings by persons with Down’s Syndrome. The competence and beauty of the works was impressive indeed. Here is a happy marriage of Allegra’s special interest in art therapy with her involvement in the winery.

On the other hand, Allegra, who recently earned her graduate degree in counseling and art therapy from Southwestern College in Santa Fe, is continuing a project that was very dear to Ann Marie: art exhibitions at the winery, but with an important difference. In March 2015 there was a display of paintings by persons with Down’s Syndrome. The competence and beauty of the works was impressive indeed. Here is a happy marriage of Allegra’s special interest in art therapy with her involvement in the winery.

For example, the works illustrated at right were all painted by Lupita Cano: (top) “Me Being Happy” 2007; (middle) “Los Magos” 2010; (bottom) “Upbeat Series #1” 2007. Various works by other artists were included in the exhibition as well.

Allegra herself seems to be on her way to becoming a label designer for Borghese’s wines. The love of art runs deep in the family.

In speaking to Bernard Ramis, the vineyard manager, it was immediately apparent that this was a man with deep roots in the French countryside who spoke with real passion of working the land and growing vines. Actually, his parents were from Spain though he was born in southern France in 1962 after they settled there. He likes to point out that he was born in the kitchen so he likes to cook. He began working in vineyards after he quit school when he was 14. By the time he was in his late 20s he had become a vineyard manager, unusual in France where one usually reaches that position at a much later age. Then he met an American woman who’d come to study winemaking and eventually they married. He came to this country in 1995 to join his wife, who’d returned to get a job in New York. He worked at a couple of prominent vineyards in Long Island before he joined Borghese Vineyards in 2004, and now has nearly 40 years of experience.

When Bernard arrived there had been no full-time vineyard manager and Mark Terry, then the winemaker, was doing double-duty in running the vineyard as well. Terry quit after about a year and an interim winemaker was hired who didn’t work out. So Marco and Bernard discussed his becoming the winemaker as well. Bernard had already worked in wine cellars and knew something about making wine, but he suggested that Borghese take on a consultant winemaker to work with them part-time, and as of 2010 that person has been Erik Bilka, a full-time production winemaker at Premium Wine Group. Bernard likes working with Erik because he finds him open-minded and ready to try new ideas. It is also, thanks to Erik’s gifts as a winemaker, that with Marco and Bernard they have the quality Borghese wines of today. Indeed, their 2013 Estate Chardonnay won a blue ribbon at the 2015 Eastern International Wine Competition.

With respect to the winemaking, Marco and Ann Marie both knew that they wanted their wine to be of a very high order of quality. Marco was very involved in the process but left the technique and skill to his oenologists, beginning with Mark Terry and then with Erik. Working with him, Marco sought to have quality over quantity, meaning low yields in the vineyards and prices fitting to the quality of the wines. As Allegra said of her father, “He had a lot of integrity.”

Indeed, Marco had deep discussions with both Erik and Bernard Ramis, his vineyard manager, to be sure that they had a clear idea of what he expected. Today, it’s Allegra and Giovanni who are having those conversations, and they deeply rely on the knowledge and experience of both men, particularly given that they well understood the standards that had been inculcated by Marco over the years. Though they’re trying to retain that approach they both know, in Allegra’s words, “that everything is an evolution when things change hands.”

For Bernard it is important that Erik trusts him to make decisions in the vineyard such as when the fruit is ready to be picked. They work well together which is important as the relationship between the vineyard manager and the winemaker is vital to the quality of the wines and the success of the winery. Bernard regards the two of them as accomplices together. For Erik the relationship is interesting in part because it involves a role reversal for him. As a production winemaker at Premium, his clients explain what they want their wines to be, usually with very precise directions about how they want them made. As a consulting winemaker, it is he who provides the instructions for how the wines at Borghese are to be made, and it is Bernard who then carries them out. All this is done with the active involvement of Giovanni and Allegra.

In the vineyard, Bernard is working with the very oldest grapevines on the Island, three acres of Sauvignon Blanc planted in 1973 and still thriving. Indeed, wine made from these vines is labelled “Founder’s Field.” 42-year-old vines tend to be shy bearers but the fruit is richer in flavor as a result. They have lived this long thanks to the quality of the soil, which despite a tendency to acidity is very amenable to the plant, and the care taken of the vineyard. As long as old vines bear enough they should, generally speaking, be kept and not pulled.

In the vineyard, Bernard is working with the very oldest grapevines on the Island, three acres of Sauvignon Blanc planted in 1973 and still thriving. Indeed, wine made from these vines is labelled “Founder’s Field.” 42-year-old vines tend to be shy bearers but the fruit is richer in flavor as a result. They have lived this long thanks to the quality of the soil, which despite a tendency to acidity is very amenable to the plant, and the care taken of the vineyard. As long as old vines bear enough they should, generally speaking, be kept and not pulled.

On the other hand, there is no Cabernet Sauvignon, for although the Hargraves planted it along with Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, the Cabernet vines died, though at the time of our interview Bernard was not sure of the cause. He had heard a story that a soil virus had attacked the vines and killed them. Bernard didn’t give much credence to that theory.

Louisa Hargrave provided this explanation in an e-mail:

“We did plant Cabernet Sauvignon the first year we came to the North Fork, in 1973:”

“The plant material we had access to was originally from Paul Masson vineyard in California but grafted at Bully Hill Vineyard in the Finger Lakes using the French-American hybrid Baco Noir as a rootstock. These plants thrived but were so vigorous that it was difficult to ripen the crop with such a massive forest of leaves. At some point, I think in the early 90s, we decided to pull out our original plantings of Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir because they were so vigorous and also because by then we were leasing Manor Hill Vineyard and so had another source of these varieties. We did not pull out the Sauvignon Blanc because it was planted on its own roots and therefore not vigorous.

“There was no soil virus. I think that idea may have come from the fact that the certified virus-free plants we bought from California in 1974 did have viruses, and were also pulled out eventually. I wrote about that particular debacle in my book [The Vineyard].”

Such were the travails of the pioneers of the Long Island wine industry.

Nevertheless, apart from the original plantings of Sauvignon Blanc and Chardonnay, and new plantings of Riesling, all the rest of the vines were pulled by Marco in 2000. Pinot Noir was then replanted that year as well as Cabernet Franc. Bernard would like to try Chenin Blanc in the vineyard as he thinks it would do well. For now, however, it is a proposal and not yet a plan.

When Bernard arrived there had been no full-time vineyard manager and Mark Terry, then the winemaker, was doing double-duty in running the vineyard as well. Terry quit after about a year and an interim winemaker was hired but he didn’t work out. So Marco and Bernard discussed his becoming the winemaker as well. Bernard had already worked in wine cellars and knew something about making wine, but he suggested that Borghese take on a consultant winemaker to work with them part-time, and as of 2010 that person has been Erik Bilka, a full-time production winemaker at Premium Wine Group. Bernard likes working with Erik because he finds him open-minded and ready to try new ideas. It is also, thanks to Erik’s gifts as a winemaker, that with Marco and Bernard they have the quality Borghese wines of today. Indeed, their 2013 Estate Chardonnay won a blue ribbon at the 2015 Eastern International Wine Competition.

With respect to the winemaking, Marco and Ann Marie both knew that they wanted their wine to be of a very high order of quality. Marco was very involved in the process but left the technique and skill to his oenologists, beginning with Mark Terry and then with Erik. Working with him, Marco sought to have quality over quantity, meaning low yields in the vineyards and prices fitting to the quality of the wines. As Allegra said of her father, “He had a lot of integrity.”

Indeed, Marco had deep discussions with both Erik and Bernard to be sure that they had a clear idea of what he expected. Today, it’s Allegra and Giovanni who are having those conversations, and they deeply rely on the knowledge and experience of both men, particularly given that they well understood the standards that had been inculcated by Marco over the years. Though they’re trying to retain that approach they both know, in Allegra’s words, “that everything is an evolution when things change hands.”

For Bernard it is important that Erik trusts him to make decisions in the vineyard such as when the fruit is ready to be picked. They work well together which is important as the relationship between the vineyard manager and the winemaker is vital to the quality of the wines and the success of the winery. Bernard regards the two of them as accomplices together. For Erik the relationship is interesting in part because it involves a role reversal for him. As a production winemaker at Premium, his clients explain what they want their wines to be, usually with very precise directions about how they want them made. As a consulting winemaker, it is he who provides the instructions for how the wines at Borghese are to be made, and it is Bernard who then carries them out. All this is done with the active involvement of Giovanni and Allegra.

From Giovanni’s point of view, while he and Allegra participate in the tasting of the batches of wine and the blends made from them, he feels that he still has much to learn but he trusts both men’s judgment and defers to them on many decisions. Largely, though, he feels that what they do decide to do is based on sound judgment and is happy to go along. After all, the most important thing is that the wines turn out well.

The basic line is the Estate wines, which include Riesling, Sauvignon Blanc, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Merlot. Reserve wines are Founder’s Field Sauvignon Blanc, Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Pinot Noir. Reserve wines are made only from grapes of the highest quality, but that doesn’t happen every year. Borghese also has a Select category for wines that don’t quite make it to the Reserve level. The line of inexpensive wines is of exceptionally good value, including a red Petite Château and a white Chardonette, at $14 and $12 respectively. They also offer two Rosés: an off-dry one called Fleurette and a dry version, Rosé of Merlot.

Castello di Borghese’s signature wines are the Barrel Fermented Pinot Noir and the Founder’s Field Sauvignon Blanc, and they have a string of award winners including Cabernet Franc, Meritage, Riesling, the Chardonnay mentioned above, and Bianco di Pinot Noir.

That Chardonnay earned its blue ribbon for its excellent balance of acidity, alcohol, and flavor. Cold-fermented in stainless-steel tanks, it underwent no malolactic fermentation so it has a purity of fruit that makes it stand out in the crowd. A delicious, refreshing wine with medium body and an agreeable mouthfeel that cries out for partnership with seafood. All this for only $18. The Founder’s Field Sauvignon is another wine that cries out for seafood; say, Peconic Bay scallops. It is grassy but lacks that intense aroma of some New Zealand versions that has been compared to “cat’s pee.” On the palate grapefruit flavors are prominent, and a bracing acidity and good balance make it a very good wine for summer drinking, even as an aperitif on its own. The tasting room staff compared it to a Sancerre, which is an apt comparison.

High-quality Italian olive oil from the family estate in Calabria can also be purchased in the tasting room.

Giovanni and Allegra have developed a natural division of labor at the winery, each doing what is most comfortable for one or the other. So Allegra has committed herself, for example, to working in the back office, designing the labels for the new wines, and so on, while Giovanni likes working up front helping to sell the wine, interacting with customers, dealing with the farm markets and things of that nature. Aware that each may have individual conversations with other persons, they make a point of bringing one another up to date so that neither is left unaware of what has been going on with the other. Together they share in all the major decisions about the direction the winery is taking.

Changes are already apparent on the Website, which has improved and offers more coverage of the winery’s events and offerings. The wines on offer are, happily, in the same style and of the same quality as before, given, of course, vintage variations. Some labels are new and some remain the same. The newest wine in the portfolio is an interesting white blend, New Moon, which is dominated by white Pinot Noir, in addition to 30% Riesling, and 20% Chardonnay. It is a distinctive blend with an unusual finish, for a white wine, of tart cherry. That, of course, comes from the Pinot Noir, which typically has a cherry nose and flavor when it is made as a red wine. The cherry, in other words, comes from the fruit and not the skins which impart red color to the red version and are not used in the making of the white: a distinctive wine with a distinctive label designed by Allegra.

Changes are already apparent on the Website, which has improved and offers more coverage of the winery’s events and offerings. The wines on offer are, happily, in the same style and of the same quality as before, given, of course, vintage variations. Some labels are new and some remain the same. The newest wine in the portfolio is an interesting white blend, New Moon, which is dominated by white Pinot Noir, in addition to 30% Riesling, and 20% Chardonnay. It is a distinctive blend with an unusual finish, for a white wine, of tart cherry. That, of course, comes from the Pinot Noir, which typically has a cherry nose and flavor when it is made as a red wine. The cherry, in other words, comes from the fruit and not the skins which impart red color to the red version and are not used in the making of the white: a distinctive wine with a distinctive label designed by Allegra.

So, the latest accolade for the Borghese Winery: 2015 Platinum Winner for Best Winery on Long Island from Dan’s Papers Best of the Best awards, which are based on readers’ votes.

As the saying goes, plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

Castello di Borghese Vineyard

17150 County Route 48 (Sound Avenue & Alvah’s Lane)

(Mailing: P.O. Box 957)

Cutchogue, New York 11935

Phone: (631) 734-5111

Toll Free: (800) 734-5158

Fax: (631) 734-5485

Owners: Allegra, Fernando, & Giovanni Borghese

Consulting Winemaker: Erik Bilka

Production Winemaker: Bernard Ramis

Vineyard Manager: Bernard Ramis

Tasting Room Hours

Daily from 11am – 5:30pm