Christian Wölffer, a real estate entrepreneur, bought the 14 acres of potato fields known as Sagpond Farms in 1978. Enchanted by the idea of a vineyard of his own after tasting a Chardonnay planted by a Sagaponack neighbor, in 1988 he asked David Mudd to plant fifteen acres of vines. It has since grown to 55 acres, with ten parcels of vines with sub-parcels. The vine rows were planted running North to South and East to West, depending on the best orientation to the sun based on the terrain. By 1996 he had assembled 168 acres, which he devoted mostly to grazing land for his horses. His first release, a Chardonnay, was in 1991.

Christian Wölffer, a real estate entrepreneur, bought the 14 acres of potato fields known as Sagpond Farms in 1978. Enchanted by the idea of a vineyard of his own after tasting a Chardonnay planted by a Sagaponack neighbor, in 1988 he asked David Mudd to plant fifteen acres of vines. It has since grown to 55 acres, with ten parcels of vines with sub-parcels. The vine rows were planted running North to South and East to West, depending on the best orientation to the sun based on the terrain. By 1996 he had assembled 168 acres, which he devoted mostly to grazing land for his horses. His first release, a Chardonnay, was in 1991.

Roman Roth and Richard Pisacano are the team that together produces some of the finest wine made in Long Island. Roman, of course, is the winemaker (and now partner) at Wölffer, and Richie—as he’s known to his friends and colleagues—is the winegrower. One is, as it were, the right hand and the other the left. So close are they that Richie’s own wine brand, Roanoke Vineyards, is made by Roman. Roman himself has his own label, Grapes of Roth, which, since he became partner this year, will be sold in Wölffer’s tasting room.

Roman has been with Wölffer Estate as winemaker since 1992, Richie came to the Estate in 1997. Both of them had years of experience in the wine trade before coming to Wölffer’s.

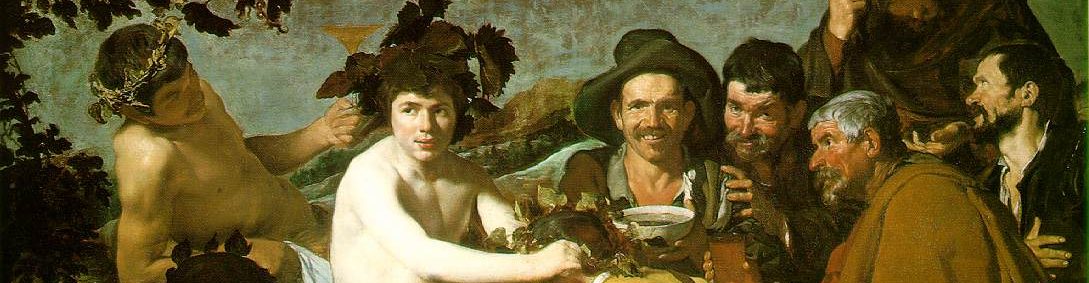

Roman & full-time vineyard crew at lunch

Roman comes from southern Germany and learned about vineyards, varieties, and vinification there, as his was a winemaking family. He travelled and worked at wineries in California and Australia before returning home. In 1992 Roman received his Master Winemaker and Cellar Master degrees from the College for Oenology and Viticulture in Weinsberg. Soon after, he accepted the position of winemaker at Sagpond Vineyards, a new winery in the Hamptons. This was a winemaker’s dream—to be part of a new and growing wine region with the chance to create something new, to leave a footprint at the foundational level.

Over the next several years, Roth managed the expansion of Sagpond Vineyards into “Wölffer Estate,” now a 55-acre vineyard with a state-of-the-art winery producing a wide range of award-winning wines, all nestled in a 175-acre property with horses, paddocks, stables, and riding trails. Under Roth’s meticulous direction, Wölffer has become a Hampton’s destination, producing wines of excellent caliber and reputation.

In April 2003, Roman received the award of “Winemaker of the Year” presented by the East End Food & Wine Awards (judged by the American Sommelier Society). This reflected the excellence of the wines he produced as winemaker and as a consultant, and was recognition of his contribution to quality winemaking on Long Island as a whole. After Christian Wölffer’s untimely death in a swimming accident, the Estate was in the hands of his children, Joey and Marc. At that time Roman was made a partner in the firm and basically runs it. In December 2015 he was elected as President of the Long Island Wine Council to serve for two years.

Rich started his career with greenhouse plant propagation, then worked for Mudd Vineyards (the first Vineyard Consulting Management firm in Long Island) in 1977, while still in high school. He went on the design and maintain vineyards for Cutchogue Vineyards (now Macari South), Pindar, Palmer, Island (now Pellegrini), Jamesport, and others before he came to Wölffer. He was invited by Roman to come to Wölffer to help “rescue” the vineyard, to help bring the Estate to the next level and further improve the quality and reputation. When he arrived he brought along with him the ideas of sustainable viticulture and in fact followed the precepts of Cornell’s VineBalance program for the last ten years.

Rich started his career with greenhouse plant propagation, then worked for Mudd Vineyards (the first Vineyard Consulting Management firm in Long Island) in 1977, while still in high school. He went on the design and maintain vineyards for Cutchogue Vineyards (now Macari South), Pindar, Palmer, Island (now Pellegrini), Jamesport, and others before he came to Wölffer. He was invited by Roman to come to Wölffer to help “rescue” the vineyard, to help bring the Estate to the next level and further improve the quality and reputation. When he arrived he brought along with him the ideas of sustainable viticulture and in fact followed the precepts of Cornell’s VineBalance program for the last ten years.

The first fifteen acres of Wölffer vines were planted by David Mudd in 1988, and it has since grown to 50 acres, with ten parcels of vines with sub-parcels. The vine rows were planted running North to South and East to West.

Wölffer’s terroir, given its location on a hill, varies considerably, much more so than the vineyards on the North Fork. The Estate has two types of soil, Bridgehampton loam and Haven.The Bridgehampton soils are mostly the flatter ground and the hillside soils, which are lighter, are mostly Haven. [i] Where the two converge one overlaps the other with interesting effects on the micro-terroir of individual vines. Both soils offer good drainage and the way that the vineyard slopes allows the cold air to flow out of the vineyard across to the Montauk Highway. With its undulating topography and overlapping soils, it makes for an especially interesting terroir, particularly so for Long Island. Rich refers to it as a “unique setting.”

Wölffer’s terroir, given its location on a hill, varies considerably, much more so than the vineyards on the North Fork. The Estate has two types of soil, Bridgehampton loam and Haven.The Bridgehampton soils are mostly the flatter ground and the hillside soils, which are lighter, are mostly Haven. [i] Where the two converge one overlaps the other with interesting effects on the micro-terroir of individual vines. Both soils offer good drainage and the way that the vineyard slopes allows the cold air to flow out of the vineyard across to the Montauk Highway. With its undulating topography and overlapping soils, it makes for an especially interesting terroir, particularly so for Long Island. Rich refers to it as a “unique setting.”

Both Richie and Roman agree that “The vineyard comes first,” and “we focus on what we can do in the vineyard, then we can make wine from that.”

The California model is not a good one to follow in LI; Wölffer has healthy low vigor/well balanced vineyards. With respect to viticulture, Rich’s is a balanced approach, with individual attention to the vines. Indeed, given his 30-years of experience, they call him “the grape-whisperer.” As Rich pointed out, in his straightforward but modest way, “given time, one develops an intuition.”

For Rich, rule number one for a vineyard manager is to throw out the personal calendar and appointment book—the vineyard has precedence over all matters personal. The Manager is like a doctor on call, always ready to respond to an emergency. Or, as Rich puts it, “Sometimes I’m not a vineyard manager as much as I am vineyard-managed.”

For example, in 2011, despite the terrible weather, including Hurricane Irene’s contribution, Wölffer had no crop loss whatsoever thanks to the adequate manpower that was available to manage the problems engendered by the weather. Wölffer managed to harvest 2.79 tons per acre, which was right at the 20-year average for their harvests. The biggest challenge of the season was the sudden changes in the weather, and that requires a very nimble and highly attentive manager.

The symbiotic relationship between vineyard manager and vintner was demonstrated in the 2005 vintage, which had been a very good season until 20 inches of rain were dumped on LI in the space of a week just at harvest time, with the result that grapes were so swollen with water that the sugar levels were diluted to as low as 16 degrees Brix. Some growers went ahead and picked the swollen grapes immediately after the rain, others abandoned entire parcels of fruit. Roman, however, saw the potential for patience rewarded and had Rich leave the grapes alone for a few days. Three days of dry weather led to the grapes shrinking back to normal size and reaching 23 Brix, and by the fifth day the sugar level had reached 25 Brix, which was unheard of in terms of sugar levels that increased so dramatically in so brief a time. At that point some of the crop began to shrivel and raisin, so a 35-person crew was sent out to pick what were now very ripe grapes. Some other vineyards had been watching what was going on at Wölffer Estate and held off as well, but none had the resources that the Estate enjoyed, so as soon as the grapes were brought in the crew was sent out to help harvest the grapes at the other vineyards as well. As a result, some very good wine was made that year, although at much smaller yields than usual. This is part of what Rich calls Roman’s “wine-rescue program.”

The fact of the matter is that Richie and Roman “get energy from one another.”

Wölffer now has seven varieties planted, including Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Merlot, Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Trebbiano and Vignoles—of which there is a half-acre. Chardonnay needs to be picked at full ripeness. In the mid-1990s the significance of proper clonal selection became better appreciated, so that optimal results can be obtained in the vineyard. Presently there are three Chardonnay clones planted: Davis 3+4 Dijon 76, and Clone 96. Dijon, which is a Burgundy clone, tends to offer comparatively low acidity by comparison with Davis 3+4, which was developed for the warmer climate of California. Merlot clones include 181 (from France), 3 (from U. of C. at Davis), and 6 (from Argentina).

Wölffer planted Trebbiano Toscano [aka Ugni Blanc] in 2010, the only Long Island vineyard to do so. The vines were productive by the 2nd year, yielding 3.5 tons / acre and by the 3rd year, 8 tons of good fruit. Given the large and experienced vineyard crew that the Estate can call on at harvest time, it was possible to harvest by hand 6 to 8 tons per hour, or about 40 tons at the end of a 7-hour day. In fact, many of the crew are people with other jobs but who have helped harvest the crop by hand for as long as ten years or more. They know what they are doing and are very efficient. According to Rich, the best of all the pickers are invariably women, who are more careful and attentive than are most of the men.

Vines’ vigor affects wine character. For that reason, there are rows of Cabernet Franc and Merlot that are reserved for making rosé that run down a slope, with Bridgehampton Loam eight feet thick at the top that is overlaid with Bridgehampton Loam as one goes down the slope, until the Haven is only eight inches thick. The Bridgehampton soils are mostly the flatter ground and the hillside soils, which are lighter, are mostly Haven. This represents ever-changing terror, which is to say that each vine in a row has a micro-terroir of its own. Indeed, thanks to drainage and soil changes along the rows, the vigor of the vines changes along the length of the slope. Consequently, in order to “harmonize” that vineyard parcel, Rich has leaf-pulling and green harvesting done along the rows at graduated intervals, with the vines furthest downslope getting the most attention, and those at the top less. Thus, the vines mature and are ready for harvest at nearly the same time. This is the work of a ‘grape-whisperer.’

Roman & crew at soccer. Goal!

Wölffer always has an adequate vineyard crew—for one thing, the Estate make harvesting fun and treats the harvest as a celebration. They feed the workers very well, with much coffee and snacks available throughout the workday. Because of so much attention in the vineyard throughout the season, there is mostly clean fruit at harvest time, which makes it easier and faster to hand-pick. In fact, a good crew can pick [clean fruit] by hand faster than a mechanical harvester is able to do. Naturally, by harvest time there are an abundance of workers available due to the fact that the tourist season has come to an end and many of the workers had been in the hospitality industry for the summer season.

Wölffer has already joined the Long Island Sustainable Winegrowers program, which leads to certification in sustainable farming. They had, as mentioned above, been growing their vines responsibly since the mid-90s, so the transition to the LISW program was actually very easy, as they’d been following the VineBalance guidelines that are the basis for the LISW ones, but modified to better fit the conditions of Long Island, rather than for the whole state of New York. For example, they do not use pre-emergent herbicides or added nitrogen to the soil—the use of nitrogen-fixing cover crops takes care of that. Periodically, given the high acidity of the Long Island soil, about 1½ tons of lime per acre is added to raise the pH level of the soil to make it more amenable for the vines. By May of 2013, the vineyard had succeeded in meeting all 200 requirements of the LISW and obtained its certification for sustainable winegrowing.

The winery is large and sophisticated, enjoying excess capacity such that not only does Wölffer buy grapes from five other vineyards, including Mudd’s vineyard, Dick Pfeiffer’s, and Surry Lane’s to make Long-Island appellation wines under the Wölffer label. Roman gets to use the winery facilities to make his own Grapes of Roth and Richie’s own Roanoke Vineyards wines. He also uses the facilities to make wine for clients Scarola Vineyards and Gramercy Vineyards as well. Indeed, in 2009 an extremely selective picking of botrytised Riesling grapes took place in Jamesport Vineyards, allowing Roman to make a TBA under his Grapes of Roth label. Not too many TBAs are made anywhere in the US of A; the very first one was a feat of the late, great Konstantin Frank, in 1965, of Finger Lakes fruit, of course, not LI. That one made headlines—in 2015 Roman’s two latest efforts with botrytised wines have earned him the highest scores ever awarded for Long Island wines.

In fact, given that Roman makes three rosés, eight whites, thirteen different reds, three award-wining dessert wines, two sparkling wines, and two apple ciders (a total of 29 different wines alone for Wölffer’s, not to speak of the wines he makes for Roanoke Vineyards), the question arises. How does he do it? Well, as he explained, working at the Karlschüle in South Germany he dealt with a wide variety of reds and whites. There he learned that close attention to detail mattered: every tank had to be topped up, every bung properly place, etc. He also gave credit to the excellent wine-growing climate of Long Island, which shares the same latitude and Madrid and Naples and gets the most sun of all of New York State. So, in early August they begin picking the grapes for sparkling wine, when they’re not fully ripe, then grapes for the rosés, which also don’t need full ripeness, and on to the whites, then the reds, which need more ripeness, and at the end of October, the late-harvest grapes. It means he has time to deal with the winemaking over a period of as much as three months. He gives as much attention to a basic white as he does to a Christian Cuvée red, because he can, all because of the enabling climate and soil.

For Roman, to make good wine demands a very scrupulous attention to detail. Not only are the grapes all hand-picked at the proper time, but when the fruit arrives at the winery they have as many as 56 hands at work at the sorting table, so no bad fruit goes into the must. Few wineries have the resources to bring more than a dozen hands to that task. When the must is fermenting in the tanks they do pumpovers three times a day, where most wineries do it only twice or even once. Of course, it helps to be able to afford a cellar team that can give this kind of time to such matters. It also helps to have had one fabulous vintage after another since 2010—2011 being the exception—and it may be true for 2015 as well.

To Roman, the great untold story about Long Island wines is their longevity: a 20-year-old Chardonnay still drinking well, for instance, and red wines that can mature and hold up for 25 to 30 years. The word has not yet gotten out to collectors that the wines of the region can be laid down and over time they will increase in value—not yet like great Bordeaux, perhaps, but as rarity and demand increase, even that is a possibility.

Roman introduced a dry rosé to the Long Island wine repertoire in 1992, within a year of his arrival at the winery—he was quite bullish in his pursuit to make Wölffer rosé a respected and fashionable wine. The 2011 is made with 54% Merlot and 21% Chardonnay, 9% Pinot Noir, 8% Cabernet Franc, 8%Cabernet Sauvignon. The 2012 consists of 69% Merlot, 16.5% Chardonnay, 5% Pinot Noir, 4.5% Cabernet Franc and 5% Cabernet Sauvignon. The blend, as one can see, varies considerably from year to year, depending on the results of the harvest. Whatever the blend, Wölffer calls it “Summer in a Bottle.”

Along with its wide range of varietal wines, including Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Chardonnay, Trebbiano, and so on, Roman also makes a non-alcoholic verjus that is a low-acid alternative to vinegar (used in a salad make the salad much more wine-friendly), but it is also an eminently quaffable beverage that is its own “Summer in a glass.” Perfect for those friends who can’t or don’t drink wine, yet almost as enjoyable.

And I cannot omit mention of the time that I stopped by at Wölffer’s tasting room to try a glass of the 2000 Merlot, which at a $100 a bottle had caused a sensation. The glass of wine cost only $25, and I sipped it slowly for over an hour, observing how it evolved with time and exposure to air. Slightly closed at first, it wasn’t long before it was offering notes of plum and black berries, and then hints of cedar and clove, becoming brighter and deeper in bouquet and flavor, and lingering long on the palate. An extraordinary wine. I knew then that Long Island wine had arrived on the world stage. I had become hooked.

And I cannot omit mention of the time that I stopped by at Wölffer’s tasting room to try a glass of the 2000 Merlot, which at a $100 a bottle had caused a sensation. The glass of wine cost only $25, and I sipped it slowly for over an hour, observing how it evolved with time and exposure to air. Slightly closed at first, it wasn’t long before it was offering notes of plum and black berries, and then hints of cedar and clove, becoming brighter and deeper in bouquet and flavor, and lingering long on the palate. An extraordinary wine. I knew then that Long Island wine had arrived on the world stage. I had become hooked.

More recently, an article on the North Forker website of July 6, 2015, “Long Island wines receive record-breaking reviews in The Wine Advocate” stated that the critic, Mark Squires, of the Advocate had awarded two Wölffer Estate Vineyard wines — the Descencia Botrytis Chardonnay and Diosa Late Harvest — the highest scores ever received in the region, each earning 94 points.

“If I had to name a ‘short list’ of top wineries in the region, this would have to be on it, without requiring any thought,” Squires wrote in his review. “Under winemaker/partner Roman Roth and Vineyard Manager Rich Pisacano (who also owns Roanoke, at which Roth is also the winemaker), this winery excels in making age-worthy, structured wines.”

“If I had to name a ‘short list’ of top wineries in the region, this would have to be on it, without requiring any thought,” Squires wrote in his review. “Under winemaker/partner Roman Roth and Vineyard Manager Rich Pisacano (who also owns Roanoke, at which Roth is also the winemaker), this winery excels in making age-worthy, structured wines.”

Further to that, in the Nov. 16 issue of Wine Spectator Wölffer’s Grapes of Roth 2010 Merlot one of the top 100 wines of the year 2015. No other Long Island winery has ever achieved that accolade. Tom Matthews wrote: “A polished texture carries balanced flavors of tart cherry, pomegranate, toasted hazelnut and espresso in this expressive red. Features firm, well-integrated tannins and lively acidity. Elegant. Drink now through 2022. 2,592 cases made.”

139 Sagg Road, PO Box 900. Sagaponack, NY 11962. Phone 631-537-5106

139 Sagg Road, PO Box 900. Sagaponack, NY 11962. Phone 631-537-5106

Wölffer Estate

P.S. – Wölffer’s also has some sample vine trellises alongside the winery. It provoked yet another post on the blog: Wölffer’s Trellis Sampler.

An excellent article about Roman Roth by Louisa Hargrave can be found at Roman History: Winemaker Profile published by the North Forker in April 2015.

[i] According to the LISW Climate & Soil Web page, “Bridgehampton-Haven Association: These soils are deep and excessively drained and have a medium texture. It is its depth, good drainage and moderate to high available water-holding capacity that make this soil well-suited to farming.”

Like this:

Like Loading...

In the words of Carol Sullivan, Gramercy “is a very pretty, pretty farm.” Gramercy Vineyards was originally a chicken farm, still with many of its original buildings, including a hen house that once kept about 50,000 chickens and a hatchery (shown above) in a separate structure. Both sweet corn and corn for feed were planted out back, as well as a hay field. The woman who later bought the chicken farm then built greenhouses and hoped to turn it into a nursery, but it never happened.

In the words of Carol Sullivan, Gramercy “is a very pretty, pretty farm.” Gramercy Vineyards was originally a chicken farm, still with many of its original buildings, including a hen house that once kept about 50,000 chickens and a hatchery (shown above) in a separate structure. Both sweet corn and corn for feed were planted out back, as well as a hay field. The woman who later bought the chicken farm then built greenhouses and hoped to turn it into a nursery, but it never happened. To help bring the animal pressure under control, Carol bought a dog from a Mississippi breeder. Cutie, is half-Jack terrier and half-Jack Russell, and is about three years old. Cutie got her name before she Carol acquired her, and at three years of age you just don’t change a dog’s name (but I dubbed her “Jumping Jack,” for she couldn’t keep still).

To help bring the animal pressure under control, Carol bought a dog from a Mississippi breeder. Cutie, is half-Jack terrier and half-Jack Russell, and is about three years old. Cutie got her name before she Carol acquired her, and at three years of age you just don’t change a dog’s name (but I dubbed her “Jumping Jack,” for she couldn’t keep still). 10020 Sound Avenue, Mattituck, NY 11952

10020 Sound Avenue, Mattituck, NY 11952