Based on interviews with Alex and Joe Macari, Jr on 9 July 2009 & 17 June 2010; updated 21 November 2014

Macari Vineyards is on the North Fork of Eastern Long Island (aka the East End) in Mattituck, and owned and operated by the Macari Family. Joseph Macari Jr., now runs the winery with his wife, Alexandra (called Alex by those who know her—but actually Alejandra, for she’s originally from Argentina). Though Macari Vineyards was established in 1995, the Macari Family has owned the 500-acre estate—bounded by the south shore of Long Island Sound—for nearly 50 years [though in 2009 they sold 60 acres of non-vineyard land, so it is now down to 440 acres]. What were once potato fields and farmland now includes a vineyard of 200 acres of vines with additional fields of compost, farmland, and a home to long-horn cattle, goats, Sicilian donkeys and ducks.

Macari Vineyards is on the North Fork of Eastern Long Island (aka the East End) in Mattituck, and owned and operated by the Macari Family. Joseph Macari Jr., now runs the winery with his wife, Alexandra (called Alex by those who know her—but actually Alejandra, for she’s originally from Argentina). Though Macari Vineyards was established in 1995, the Macari Family has owned the 500-acre estate—bounded by the south shore of Long Island Sound—for nearly 50 years [though in 2009 they sold 60 acres of non-vineyard land, so it is now down to 440 acres]. What were once potato fields and farmland now includes a vineyard of 200 acres of vines with additional fields of compost, farmland, and a home to long-horn cattle, goats, Sicilian donkeys and ducks.

Macari sees itself as on the cutting edge of viticulture and has long been committed to as natural an approach to winemaking as is possible. Since 2005 Joseph Macari, Jr. has been considered as a pioneer in the movement towards natural and sustainable farming on Long Island, employing principles of biodynamic farming beginning with the vineyard’s first crops. By giving consideration to the health of the environment as a whole and moving away from the noxious effects of industrial pesticides towards a more natural and meticulous caretaking of the soil and plants, Macari believes that it has found a more promising way to yield premium wines (recalling the old French axiom, that wine begins in the vineyard). This does not mean that Macari claims to be producing organic grapes, nor organic wines—that, in Joe’s view, is not possible for a vineyard of its size in Long Island, given the climate, with its high humidity and much rain during the growing season, both of which tend to encourage the ravages of fungal and bacterial infections of the vines, as well as attacks by a range of insects.

My first visit was in July of last year, and my follow-up visit was this June. We started in the new and modern Tasting Room at the Winery. Alex, as Joe’s wife is called) began with a tasting of a range of Macari wines, all of which were well-made and at the least, quite good, with some of very fine quality, well-balanced, with good acidity and fruit. The winery produces both barrel-fermented and steel-fermented whites as well as barrel-fermented reds and a couple of cryo-ice wines (“fake” ice wine, as Alex teased, but Joe is an enthusiast, and the wine is actually delicious and has won awards). In fact, the winery employs two winemakers, one of whom is Austrian and makes the steel-fermented whites as well as the ice wines. (I’ll review the wines when I write about wine-making at Macari in a separate post.)

The vineyard tour in a 4-wheel-drive pickup truck began with an exploration of the composting area, where manure from the farm animals is gathered (cows—including long-horn steers—horses, and chickens) as well as the vine detritus (which is charred in order to render any infection or harmful residue neutral), and 35 tons of fish waste that is delivered once a week by a Fulton Fish Market purveyor (Joe says that the fish guts & bones provide excellent nitrogen & DNA for the compost, so it is highly nutritive for the vines). At the time of my visit the compost heaps—some of which were from six to eight feet high—were covered in weeds, which will be removed before the compost is applied as fertilizer.

The vineyard tour in a 4-wheel-drive pickup truck began with an exploration of the composting area, where manure from the farm animals is gathered (cows—including long-horn steers—horses, and chickens) as well as the vine detritus (which is charred in order to render any infection or harmful residue neutral), and 35 tons of fish waste that is delivered once a week by a Fulton Fish Market purveyor (Joe says that the fish guts & bones provide excellent nitrogen & DNA for the compost, so it is highly nutritive for the vines). At the time of my visit the compost heaps—some of which were from six to eight feet high—were covered in weeds, which will be removed before the compost is applied as fertilizer.

In order to save time and space—two valuable commodities in growing wine grapes—vineyards sometimes graft new vines onto a mature rootstock, rather than starting an entirely new plant. According to the Macari Website, theirs is the first vineyard on Long Island to successfully grow over-grafted vines. With over-grafting, a new variety can be grown from the rootstock of a different plant, which is a much faster way of growing vines than planting new ones. The future of every vineyard depends on the carefully executed process of planting new vines. Macari’s vision of the future is constantly evolving as the owners, vineyard manager and winemaker learn more about their vines, and the microclimates found in the fields.

The vineyard proper is very well-tended, the various varieties separated into blocks, using Vertical Shoot Positioning (VSP), and in many parcels irrigation tubes were carefully aligned along the bottom wires of the rows to provide drip irrigation if necessary, though the high humidity and rainfall of the region reduces the likelihood of needing its use. In fact, the 2009 season thus far has had such an excess of rainfall—often very heavy—that in many parts of the vineyard there was blossom damage and many of the developing bunches of grapes were, in effect, incomplete due to fruit loss.

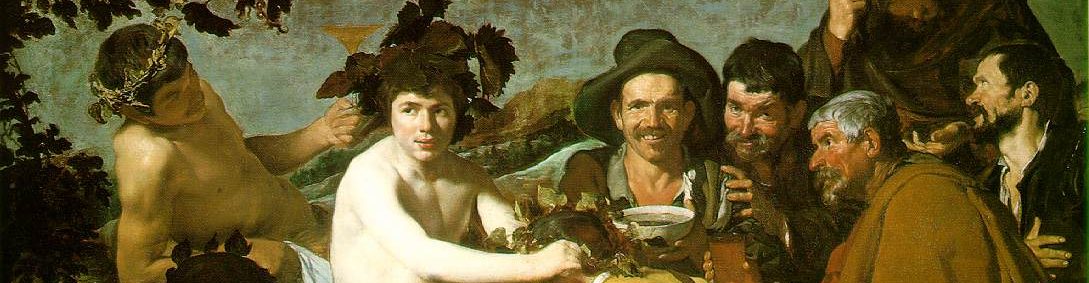

Joe has been using, to the extent possible, both organic and Biodynamic® methods of viticulture, but due to the highly-humid conditions in the vineyard, he must still resort to conventional sprays from time to time, so he refuses to claim to be organic or biodynamic, though he finds that to the extent that it is possible to use these viticultural methods, it is worthwhile. For one thing, Joe worships Mother Earth, and believes in the Rudolf Steiner principle that there ought to be a harmony between earth, sky, and water, and in consequence has resorted in the past to planting cow horns at the ends of rows, with the requisite composting “teas” that are recommended by the biodynamic movement. He plans to return to this practice again in coming years. Though Alex appears to be skeptical of the remedy, the special attention and care demanded by organic and biodynamic practice are evident in the vineyard, as can be seen in the picture above, which shows the cover crop extending from between the rows right into the vines themselves, weeds and all, in order to allow the greatest amount of vegetative variety and expand the quantity of beneficial insects and other fauna to find their natural habitat.

Another reason that Macari does not seek Organic Certification is economical. It is one thing to apply expensive organic sprays on, say a 20-acre field, quite another to do so on 200. The sprays cost twice as much as the industrial alternatives and the spraying would involve higher labor costs, as the number of times that the spray needs to be applied would be higher than for conventional applications. Furthermore, the fact that you can practice organic and/or biodynamic farming without going for 100% organic—being pragmatic about using industrial sprays when absolutely needed, but otherwise being committed to organic ones when it is suitable—means that you can have a sustainable, healthy vineyard in almost all respects.

In other words, as Joe sees it, Organic Certification may be economically viable for a small vineyard, but is much less so for large ones.

One additional bit of evidence regarding the exceptional care given the Macari vineyards is the employment of a team of specialized grafters from California, who travel around the country—and the world—grafting new shoots to old roots, so that, for example, a field of Chardonnay can be quickly converted to Sauvignon Blanc. The process is highly meticulous, requiring special knowledge of the condition of the roots. For example, in the case of a root with splitting bark, one type of graft and wrapping may be applied as opposed to another for a root that doesn’t suffer from the problem. This team of five men can graft about 500 roots a day at a cost of $2.00 per root—a highly efficient rate that is cost-effective for the vineyard. (This team had earlier been working in Hawaii, and has also done grafting for Château Margaux—yes, that one in Bordeaux of 1855 Classification fame—and at the same time was working at Peconic Bay Vineyards nearby.)

One additional bit of evidence regarding the exceptional care given the Macari vineyards is the employment of a team of specialized grafters from California, who travel around the country—and the world—grafting new shoots to old roots, so that, for example, a field of Chardonnay can be quickly converted to Sauvignon Blanc. The process is highly meticulous, requiring special knowledge of the condition of the roots. For example, in the case of a root with splitting bark, one type of graft and wrapping may be applied as opposed to another for a root that doesn’t suffer from the problem. This team of five men can graft about 500 roots a day at a cost of $2.00 per root—a highly efficient rate that is cost-effective for the vineyard. (This team had earlier been working in Hawaii, and has also done grafting for Château Margaux—yes, that one in Bordeaux of 1855 Classification fame—and at the same time was working at Peconic Bay Vineyards nearby.)

As a further example of the globalization of viticultural practices, Joe also has a French specialist in tying vines to the trellising system come from Southern France with his own team in order to train his Guatemalan workers in how to properly tie vines to the wires, for it must be done properly if the vines are to be held to the wires for the duration of the growing season.

To the extent that one can achieve balance with nature in viticulture (or in agriculture as whole), Joe Macari has certainly shown that he in the vanguard of that search. It is not for the sake of certification, either organic or biodynamic, that he does this, but out of respect for his vineyard’s terroir, which is to say, the land, the soil, the vines, the climate. But all viticultural work involves experimentation, and Joe is always experimenting, as new ideas and information become available to him. There is always a better way. The pursuit is endless, and the story therefore never ends.

To the extent that one can achieve balance with nature in viticulture (or in agriculture as whole), Joe Macari has certainly shown that he in the vanguard of that search. It is not for the sake of certification, either organic or biodynamic, that he does this, but out of respect for his vineyard’s terroir, which is to say, the land, the soil, the vines, the climate. But all viticultural work involves experimentation, and Joe is always experimenting, as new ideas and information become available to him. There is always a better way. The pursuit is endless, and the story therefore never ends.

PS–For another recent appreciation of Joe Macari’s work, see the informed and thoughtful account by Louisa Hargrave in the January 14, 2010 issue of the Suffolk News at https://www.macariwines.com/macari.ihtml?page=awards&awardid=184

Louisa also wrote a very nice profile of Kelly Urbanik Koch, Macari’s resident winemaker, in the Winter 2014 issue of Long Island Winepress: Meet your winemaker Kelly Urbanik Koch of Macari Vineyards/

Louisa also wrote a very nice profile of Kelly Urbanik Koch, Macari’s resident winemaker, in the Winter 2014 issue of Long Island Winepress: Meet your winemaker Kelly Urbanik Koch of Macari Vineyards/

In fact, a favorite wine of ours offered at the New York Uncorked wine tasting was a really sublime 2013 Sauvignon Blanc by Kelly—deeply perfumed with floral aromas and the typical Sauvignon flavor profile beautifully tamed with a fine balance of citrus fruit and floral notes against a firm acidic backbone. The best American SB that I can remember, frankly. Kelly was so happy with the result that she said that she wished that she could “swim in it”–in a tank, to be sure.

In the summer of 2014, Macari was named New York State Winery of the Year at the NY Wine & Food Classic, a tasting competition of over 800 wines from across the state’s viticultural areas. Macari’s 2010 Cabernet Franc was named by the competition’s judges as the Best Red Wine of the show.

Mattituck Winery

150 Bergen Avenue, Mattituck, NY 11952

(631) 298-0100

Cutchogue Tasting Room

24385 Route 25, Cutchogue, NY 11935

(631) 734-7070

We'd like to thank your for a great article outlining our approach to farming and treatment of our estate. We are all firm believers that more natural methods of farming will ultimately yield better fruit, and in turn quality wines. Hope to read more about LI viticulture and hope to see you in our tasting room!

The Macari Staff